I was unaware of this change until it reached a critical mass. It may have seemed sudden, but the transition from inflammable to flammable took several decades. The Ngram, graphed below and discussed by The Grammarist, shows that flammable overtook inflammable somewhere around 1978, at least in the publications Google includes in their corpus.

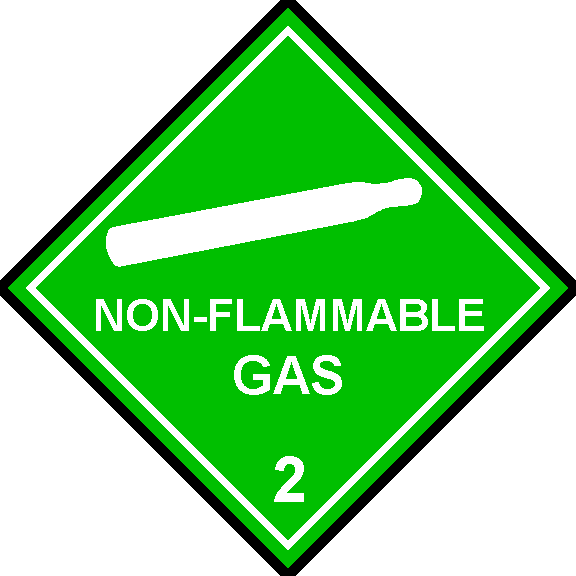

The change occurred to avert possible misinterpretation of the danger signs. (Tap on the graph curve to show stats by year.)

So, inflammable is in transition, losing its prefix in-. In American-English, the transition is nearly complete. However, the related derivations retain the prefix, as with inflammatory, inflammation, inflammability. This word is also related through the root to inflame, inflaming, and the French loan words flambeau, flambé and flamboyant. See more words from the FLAM root family at Word Info. (See comments for discussion of possible spelling of base as FLAMM.)

Misinterpretation occurred because of the prefix in-. The word inflammable is parsed into in- + flam + -able. The root FLAM denotes 'to kindle, to set on fire, to burn.' This word came to English via Latin by way of French. The prefix in- comes in several spelling forms: in- (indirect), im- (improper), il- (illegal), and ir- (irreligious).

The prefix in- has three meanings or interpretations. The most commonly used sense conveys 'not' or 'non' as in insensitive, inedible, illegal, implausible, irreverent, etc.

The secondary meaning for the prefix in- is 'into, in, on, upon' as in insert, incandescent, and implant.

The third sense of the prefix is qualitative. Sometimes it serves as an intensifier, much like we use very or extremely.

So, basing word meaning strictly on the meanings of each morpheme, inflammable could be interpreted in three possible ways:

- 'not flammable'

- 'flammable from within, able to burst into flame'

- 'extremely flammable'

The second and perhaps even the third options are correct; inflammable indicates that something is "flammable from within, able to burst into flame, able to be set on fire." See Online Etymology Dictionary.

But apparently, and understandably, some folks thought inflammable meant 'not flammable' just as inedible means 'not edible.' So, the decision was made to change the danger signs. Gasoline and other combustibles are fairly consistently labeled FLAMMABLE. Today, FLAMMABLE and INFLAMMABLE are synonyms. They mean the same thing. They both warn of fire. But FLAMMABLE is seen far more frequently.

But apparently, and understandably, some folks thought inflammable meant 'not flammable' just as inedible means 'not edible.' So, the decision was made to change the danger signs. Gasoline and other combustibles are fairly consistently labeled FLAMMABLE. Today, FLAMMABLE and INFLAMMABLE are synonyms. They mean the same thing. They both warn of fire. But FLAMMABLE is seen far more frequently.

To make meaning quite clear, non-combustible materials that are not flammable are now termed non-flammable, thus avoiding the polysemous prefix in- completely. Why muddy the waters with the negative sense of the prefix in- when we have only just clarified things? And using green for the signage helps to convey the meaning. A safe color, green is go.

FLAMMABLE = INFLAMMABLE = FIRE RISKBecause inflammable derives from Latin, it is likely to have some look-alikes or cognates across the Romance languages. But when it changed to flammable in English, did it also change in Spanish? In French? In Italian? Not so much. See signs.

To reduce confusion, perhaps we should just do away with words and communicate through pictures, icons, signs. This involves semiotics, the study of how signs, symbols, and icons are interpreted and used to convey meaning. A sort of "sign-ology" (not to be confused with scientology).

Before Bill Bryson kindled my interest in morphology and word origins with his engaging if not authoritative book, The Mother Tongue: English and How it Got That Way, I assumed inflammable was just a poorly constructed word. I did not realize that the prefix in- had more than one meaning; instead, I consistently interpreted the prefix to mean 'not'.

But take note! This confusion did NOT cause me to underestimate the danger, spelled out on red cans and orange signs: Given what I know about the world (ah, so we infer!) and particularly about gasoline, I decided I would simply have to ignore the pesky prefix and go with my gut. Those gas pumps are gonna readily burn even though the warning sign does not seem to indicate so.

Perhaps my own coming to terms with inflammable sheds a little light on how we all process language. When it comes to words, one of the questions linguists debate is which is processed first or the fastest and/or to the greatest extent, the whole word or the morphemes that make up the word? Well, both, actually. In addition, it is context that floats our language boat. Thus, one of my favorite reads: In the Beginning was the Word (Aronoff, 2007) and, I dare to add, "In the End, the Word" and "Along the Way, the Morphemes."

Implications for Teaching Vocabulary: Teach students whole words. Also, teach them morphology (prefixes especially). Teach them to pay close attention to context. Help them learn to trust their own gut--to develop self-efficacy when interpreting word meanings, by drawing clues from context and from morphemes, and from knowledge of the world. Also, teach them to use a dictionary when needed. This aligns with the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts. Here is an example from grade 5:

COMMON CORE STANDARD: Vocabulary Acquisition and Use L.5.4.

Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases based on grade 5 reading and content, choosing flexibly from a range of strategies.

- Use context (e.g., cause/effect relationships and comparisons in text) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase.

- Use common, grade-appropriate Greek and Latin affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of a word (e.g., photograph, photosynthesis).

- Consult reference materials (e.g., dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to find the pronunciation and determine or clarify the precise meaning of key words and phrases.

Also, encourage students to read, especially during the summer. Play word games (so many cool apps for word play--my newest fave is "4 Pics 1 Word"). Kindle interest in words, phrases, and language in general.

See also The Popular Prefix Survey Results