This post is courtesy of Dr. P. David Pearson. David is a faculty member in the programs in Language and Literacy and Cognition and Development at the Graduate School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley, where he served as Dean from 2001-2010. Current research projects include Seeds of Science/Roots of Reading -- a Research and Development effort with colleagues at Lawrence Hall of Science in which reading, writing, and language are employed as tools to foster the development of knowledge and inquiry in science--and the Strategic Education Research Partnership (SERP)--a collaboration between UC Berkeley, Stanford, and the SFUSD, designed to embed research within the portfolio of school-based issues and priorities. Across his career, David has earned numerous awards for his contributions to reading research. He is the founding editor of the Handbook of Reading Research, now in its fourth volume. David taught elementary school in California for several years.

I have been a fan of vocabulary, both as a conceptual/theoretical issue and as an instructional phenomenon, for well over 40 years. I have always loved dictionaries, and thesauruses even more. And I never ceased to be amazed at how easily vocabulary maps onto our conceptual understanding of the world(s) in which we live, both the natural world that surrounds us and the intellectual conceits that we create in our imagined worlds.

I have this vivid recollection of a conversation between me and two ardent whole language advocates in 1977, just a few months after Dale Johnson and I published a book entitled, Teaching Reading Vocabulary, in which we made a case for the explicit teaching of words in several senses and contexts. "How could you publish a book about words?" they complained. "Words don't really exist, except as a convenient orthographic convention. And in writing about words, you encourage teachers to focus on them rather than on the meaning of text." So went the battle for about two hours (along with a good bottle of Cabernet, as I recall, maybe two!). Neither they nor I changed our positions. They still don't like words, and I do. But it did make me think about why I think vocabulary is so important. And it's because words aren't the point of focusing on words. Meaning is! But words are the convention we have adopted as a species (and words really are a universal component of language) for naming the meanings we wish to point to, highlight, feature, and discuss. And so it is not words for words' sake, but words for the doors of meanings they open for us that really matters.

|

| Click to enlarge |

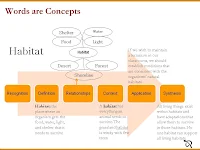

In my own recent work with Gina Cervetti and others at Lawrence Hall of Science at UC Berkeley, we are working on the role of word learning as an instance of the acquisition of conceptual knowledge about science. And that has led us to our own theory of the development of conceptual knowledge/word meaning, shown here. This is slide 55 of Science and Literacy.

The basic idea is that we have to encounter words in many settings in order to "own" it: (a) as a "representation" to pronounce or decode, (b) as a "definitional" entity (where a definition is something like a "summary" of one's word knowledge), (c) as an entity that we meet in a range of oral, written and experiential contexts, (d) as a part of a semantic network of related concepts/words, (d) as a "sign" we use when we DO something in the world (I have learned, in my work on the role of language in hands-on science, that this embodied connection is much more important than I ever thought it might be), and (e) as a label we use when synthesize our knowledge about a topic or an experience. That is the essence of slides 54-55 in the Powerpoint presentation at this link. To that list, if I were revising that slide knowing what I have learned from Susan Ebbers, I would add a morphological setting in-between the definitional and the semantic settings.

All of these settings are important, none moreso than any other. The simple truth is that when it comes to learning vocabulary, nothing beats exposure and use--in every possible learning modality. In Seeds and Roots, we say, when it comes to learning new vocabulary, Read it! Write it! Talk it! Do it! There is no better--maybe no other--way.

That's all for now. Thanks, Susan, for giving me a little space in your blog. Look forward to hearing from lots of you.

David